The story of the Great Rift Valley begins deep in time, when the African continent first began to pull itself apart. Invisible yet relentless forces stretched the crust, cracking it open from the Red Sea southward through the heart of the continent. Along that shifting spine lie some of Africa’s most astonishing landscapes, each a different expression of the same restless geology.

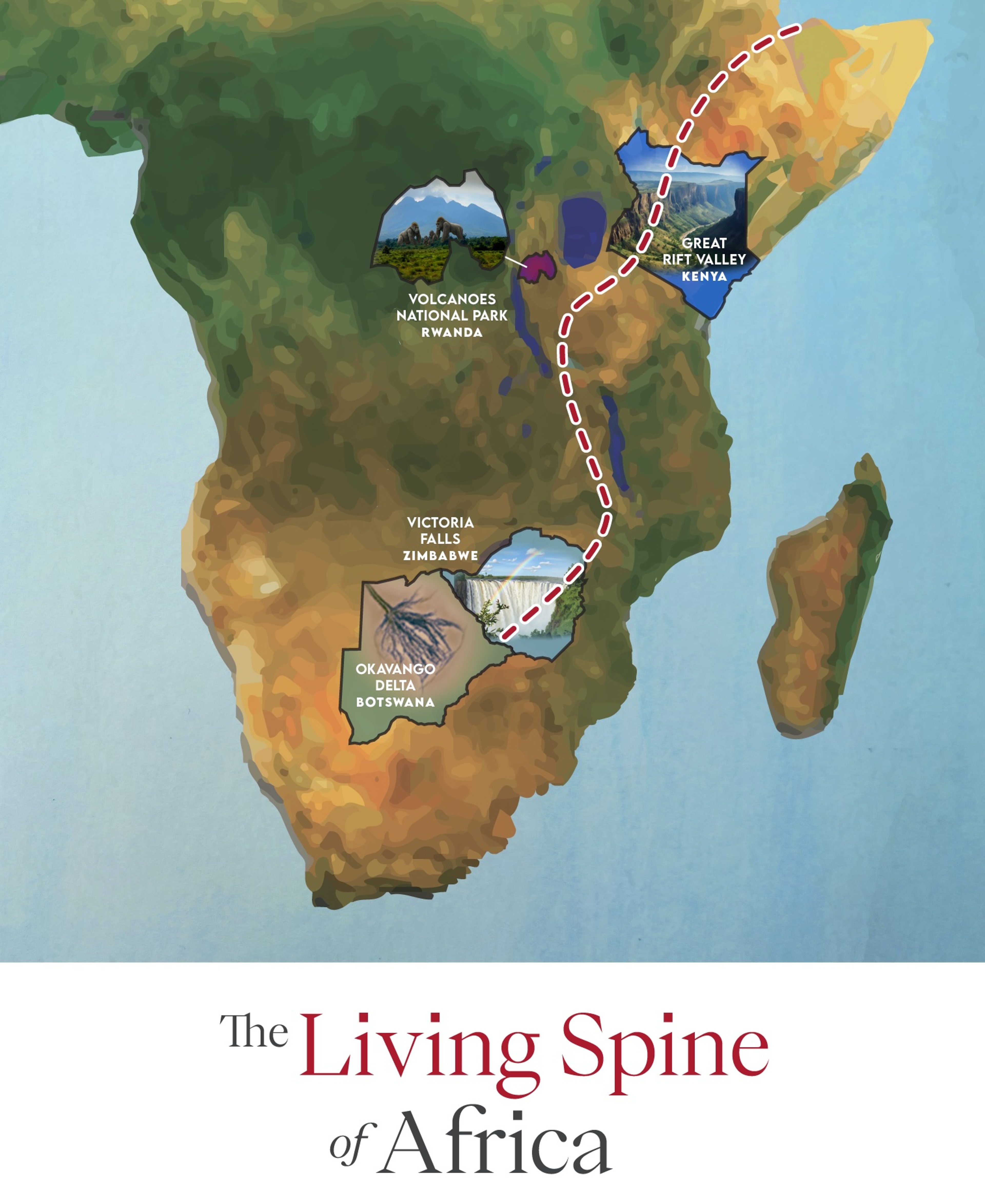

Imagine 3,728 miles of valley where Africa is very slowly splitting in two. Along that valley lie roaring waterfalls, endless plains and volcanoes. That is the Great Rift Valley. And it is not a single valley, but a vast tectonic system stretching from the Middle East down through East Africa to southern Africa, formed by the slow pulling apart (rifting) of the Earth’s lithosphere.

When designing The Greatest Safari on Earth℠, we traced this living spine in a journey not just across Africa, but along the path that shaped the continent and humanity itself.